In order to understand your stress type, it’s important to zoom out and look at the entire spectrum of how the body responds to stress.

Simply defined, stress is the body out of balance. We all have a baseline. Good or bad external events and internal thoughts can push the body out of balance, shifting us away from that baseline. Such events - or stressors - trigger the brain to perceive and respond with the goal of bringing the body back to baseline. What goes up must come back down.

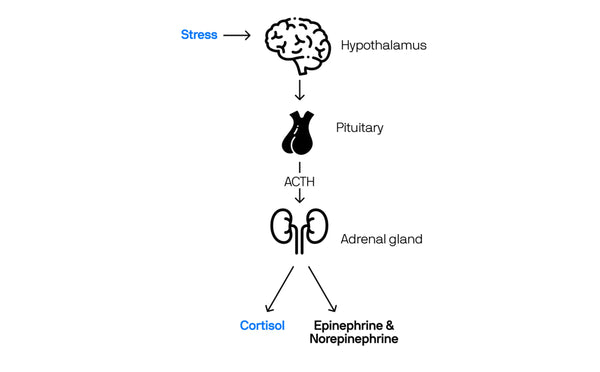

Our bodies are amazing. They have a sophisticated means to respond to acute stress through the HPA-Axis (hypothalamus, pituitary, adrenal axis) (1). Think of the HPA as a connected network of endocrine glands, hormones, and other signaling molecules that talk back and forth with each other, like an airport control tower communicating with planes. The problem arises when we experience chronic, unrelenting stress. We’ll get to that in a minute.

First, let’s look at the steps of how the body responds to stress. This involves an interconnected system that begins in the brain. You have two branches of your nervous system:

Nervous system branches:

- FIGHT or FLIGHT (Sympathetic Nervous System)

- Rest, Digest, Heal (Parasympathetic Nervous System)

Stress activates the sympathetic branch of the nervous system through the HPA-axis.

The Stress Response via HPA-Axis

1. Hypothalamus. Control Tower 1.

This part of your brain is constantly monitoring internal and external signals, like an airport control tower. When the hypothalamus perceives a stress signal, it releases a signaling molecule, corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF), that passes information to another controller at the tower, the pituitary gland “Attention Control Tower 2. We have stress.”

2. The Pituitary Gland. Control Tower 2.

The pituitary gland releases a second signaling molecule, adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH), that travels through the bloodstream to the adrenal glands (little almond shaped-glands that sit on top of the kidneys). “Southwest flight 522, this is the control tower 2. It's time to hit the engines. Clear for takeoff”

3. The Adrenal Glands. Planes on the Runway.

The adrenal glands get the message from the pituitary and respond by making a group of hormones called corticosteroids, the most important being cortisol and a stimulatory neurotransmitter, adrenaline. Cortisol is an anti-inflammatory hormone that has a role in regulating sleep-wake cycles, blood sugar, blood pressure, stress response and how your body uses carbs, fat and protein as energy.

The release of cortisol and adrenaline in the bloodstream activates different receptors throughout the body and leads to a variety of behavioral and physiological changes to prepare the body to respond to the stressor including (1):

- Increased heart rate

- Increased respiratory rate (breathing speeds up)

- Vasoconstriction of blood vessels which: increases blood pressure; leads to cold, clammy skin

- Release of glucose to feed muscles for activity (fight or flight)

- Decreased digestive activity

- Increased awareness

- Decreased pain perception

- Improved cognition

- Decreased immune function

Once the stressor has been dealt with, levels of cortisol and adrenaline return to normal ranges and all physical and mental adaptations normalize through the parasympathetic nervous system. This is an optimal stress response.

What happens when the body experiences chronic, unrelenting stress?

Work deadlines. Financial pressures. Toxic relationships. These can all produce chronic stress.

Our bodies are maladapted to respond to this type of a stress pattern driven by psychological stress. Chronic stress can start us down a path that negatively impacts our health.

Chronic Stress Health Risks (2):

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Heart Disease

- High Blood Pressure

- Digestive disorders including IBS

- Insulin resistance & Diabetes

- Weight gain

- Insomnia

- Cancer

- Frequent infections

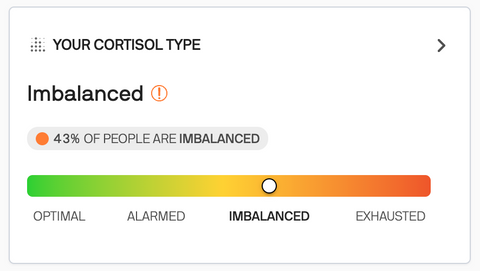

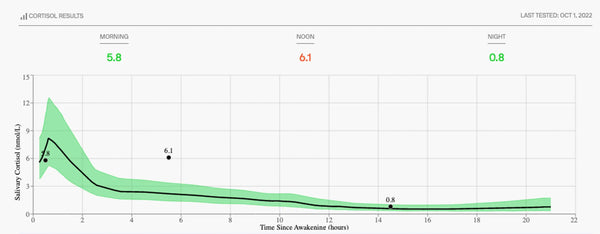

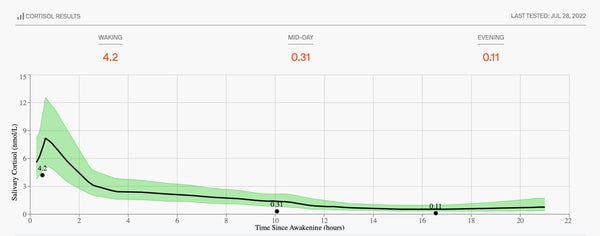

In order to combat chronic stress, it’s important to understand where you are on the Stress Spectrum. A multi-point salivary cortisol test can be conducted to chart your personal stress pattern. Once you understand your stress type, you can begin to implement recommendations to bring your body into balance.

Let’s take a look at the stress spectrum and learn about the different stress types.

Rootine's Stress Spectrum

Stress Type: OPTIMAL

In an optimal stress response, the body can properly communicate via the HPA-axis, raising the alert (fight-or-flight) message to respond to the stressor and then returning to balance.

What this can feel like:

An optimal cortisol curve demonstrates this pattern with a robust cortisol-awakening response 30-minutes after waking. The rise in cortisol wakes you up from sleep and activates your brain for the day.

Following the rise in cortisol, your body will follow a controlled downward slope during the day with adequate, balanced cortisol that maintains afternoon energy and gently decreases around bedtime to allow for great sleep. Cortisol and melatonin have an inverse production and relationship. Cortisol = awake and alert. Melatonin = relaxed and asleep.

This optimal pattern reflects a body with high resilience, proper mental and emotional response to stress, and a balanced lifestyle with optimal stress - remember, stress can be good too and we need some!

Stress Type: ALARMED

When the stress response extends past a short-lived event to chronic stress, the body begins to tip out of balance. This leads to the first pattern of a dysfunctional stress response, or HPA-axis dysfunction (HPA-D).

During phase 1 of the chronic stress response the body gets stuck with the smoke detector on. Constant alarm signals lead the adrenal glands to produce large amounts of cortisol and adrenaline.

What this can feel like:

Increased processing speed of the brain can initially lead to increased focus and concentration but quickly progresses to overwhelm and tension as the brain perceives everything from a place of system overload. Basic things like dripping water, background chatter, and the tapping of a pencil soon can become too much.

With increased cortisol and adrenaline, blood pressure and perspiration increases and heart rate rises, sometimes with an increase in body temperature. This can lead to an overall feeling of anxiety, tension and overwhelm making it difficult to focus and get tasks done.

Cortisol signals an increase of glucose from the liver to feed muscles and the brain. It is common for individuals in ALARM to experience less hunger or imbalanced hunger signals due to changes in blood sugar. Blood glucose testing may show elevated levels in this stage of the stress response.

Cortisol levels tend to be normal to high at different points of the day in HPA-D pattern as this is the ALARM or activation stage of HPA-D. Individuals in ALARM may have elevated cortisol levels at night that leave them feeling wired, making it hard to fall asleep. This can lead to a pattern of being a night owl and drive an individual into the second phase of the stress response.

Stress Type: IMBALANCED

In the second phase of the stress response, there is an inconsistent production of cortisol and adrenaline throughout the day and HPA-D progresses as chronic stress persists for a moderate period of time. This phase of the stress response is the most varied, with cortisol levels bouncing above and below normal at different points of the day leading to a large variety of symptoms.

What this can feel like:

Many individuals describe the feeling of being TWIRED, Tired & Wired, during phase 2 which is consistent with variable amounts of cortisol and adrenaline. In earlier parts of phase 2, individuals may feel energy in the morning with a big afternoon crash finishing and a surge of energy in the evening.

As phase 2 progresses and the body becomes more fatigued, individuals may feel groggy in the morning (hit that snooze 3 times) due to lower cortisol production. They may also experience mid-afternoon energy crashes accompanied by strong caffeine and sugar cravings as the body attempts to raise adrenaline levels. This chronic fatigue also results in rising brain fog and poor exercise recovery (feeling extra sore, breathing heavier during cardio). The need for an afternoon nap with a second wind around 9pm is a common reporting for the Imbalanced Stress Type.

Without proper intervention, Imbalanced can progress into the Exhausted stress type.

Stress Type: EXHAUSTED

By the third phase of stress response, your body has been under chronic or severe stress for a prolonged period of time, leading to suboptimal hormone production that can include cortisol, adrenaline, sex hormones, and other neurotransmitters. The third phase is reached after passing through phase 1 and 2. By this point, the body has exhausted its resources causing lower than normal levels of cortisol throughout the day.

What this can feel like:

Individuals in Exhausted Stress Type tend to experience all-day fatigue and report feeling run down and depleted. It is hard to get up due to low to no cortisol awakening response. Other common symptoms include blood sugar imbalances and food cravings (salt and sugar as aldosterone levels can be altered), as well as insomnia at night and high desire for daytime naps due to altered melatonin production. Exercise intolerance can be severe with feelings of oxygen hunger if the body is pushed too hard. Brain fog can be severe and debilitating.

At this stage of the stress response, health issues start to arise including3:

- Mood changes, including more depressive tendencies from lower neurotransmitter production4

- GI issues from increased gut permeability (IBS, food sensitivities and allergies)5

- Weight gain, insulin resistance, and diabetes

- Immune imbalances and more frequent infections

- Menstrual cycle irregularity due to changes in sex hormone production

- Higher inflammation (from low cortisol)

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chemical sensitivities, allergies

- Pain conditions

The Exhausted Stress Type requires a comprehensive plan for recovery with more support in the lifestyle, diet, hydration and supplementation realms.

Do your results seem inconsistent with your experience?

Believe it or not, this is a common question/response. And there are several things to explore.

- Did you test on a normal day?

Cortisol is ever-changing in all of our bodies. If you had an intense workout, a big project at work, a fight with your partner, a long travel day, or consumed more alcohol than normal, your results may be out of normal for you.

If you find this to be true, we suggest that you retest on a normal day.

- Stress Perception

Stress is a common denominator for all of us on planet earth. How we perceive and respond to stress is completely unique. Some of us are optimists, the cup is always half full! This can serve you well in life but it's important to note that the body has a memory and may register your stress differently and more intensely. This can lead to a more progressed stress type reporting than you “feel”. On the other hand, some people are very sensitive to stress and may feel more worn out by stress than their body shows on a test. The great news is: recovery can be fast!

Need help navigating your next steps? Have further questions? Schedule a free 15-minute consult with a clinical nutritionist (Rootine Health Coach).

- There may be other underlying factors

The body is dynamic and interconnected. If your cortisol results do not line up with your experience/symptoms there may be something else going on. This could include other conditions like your thyroid, gut, sleep apnea and more. It is important to talk to your healthcare professional about your questions and concerns.

Still have questions? We are here for you. Reach out here through your dashboard.

Sources

- 1. Sean M. Smith. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006 Dec; 8(4): 383–395. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.4/ssmith

- Mohd. Razali Salleh. Life Event, Stress and Illness. Malays J Med Sci. 2008 Oct; 15(4): 9–18. PMID: 22589633

- Kara E. Hannibal, Mark D. Bishop. Chronic Stress, Cortisol Dysfunction, and Pain: A Psychoneuroendocrine Rationale for Stress Management in Pain Rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 2014 Dec; 94(12): 1816–1825. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20130597

- Ewelina Dziurkowska, Marek Wesolowski. Cortisol as a Biomarker of Mental Disorder Severity. J Clin Med. 2021 Nov; 10(21): 5204. doi: 10.3390/jcm10215204

- Aitak Farzi, Esther E. Fröhlich. Gut Microbiota and the Neuroendocrine System. Neurotherapeutics. 2018 Jan; 15(1): 5–22. doi: 10.1007/s13311-017-0600-5